After The Long Day

With the recent passing of Terence Davies, Roxy Cinema thought it an apt time to show The Long Day Closes on 35MM. Matt Haller writes a personal account of what the film and Terence Davis meant to him.

___

At half-past five in my childhood home, the sun would set perfectly to where it would cast beams onto the carpet below, shimmering as leaves rustled against the light. I had just finished watching a film, as I always did most days after school in order to avoid my homework. It was the end of my senior year, two months from graduation. I spent most of high school sheltered from the world—closed off because of my sexuality, which I felt was not valid in the world. I was queer, and hated the fact that I was queer. I had settled into my identity when I’d met my partner at the time. But we were drifting, and I was no longer happy in that relationship, scared to admit it to myself. I fell back into my old ways of self-hatred.

I was called down to the kitchen. Downstairs was my mother in a panic, running around the house gathering up various items. My younger sister had been struggling with her mental health for a long time—practically all our lives—and her mental health had worsened. My mom was packing to be with my sister, who was in the hospital. She had locked herself in the bathroom at school that day, and threatened to take her own life. Panting and holding back tears, my mother explained this all to me while I stood frozen in the kitchen. Within five minutes she was gone. I was too shocked to speak.

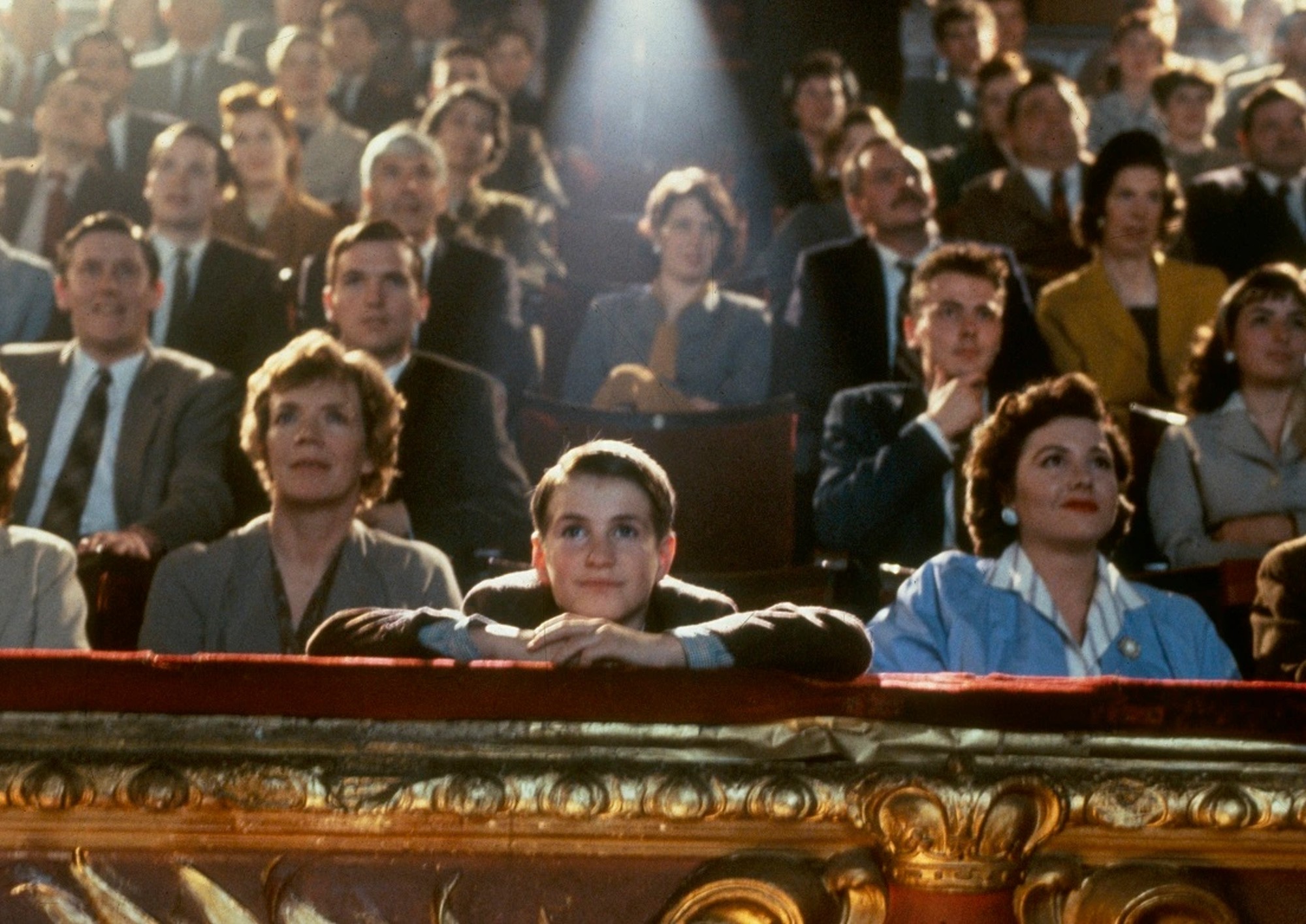

As with all low points of my life, I turned to the only thing that paved the way for my future; cinema. I was locked in my room, now pitch black, scrolling through the Criterion Channel in search of a film to guard me from my reality. After an hour of searching (at least, what felt like an hour), I landed on the image of a boy pushed up against a faded green wall. I clicked play, opening on the image of a bouquet, much like a painting within my grandparents’ old home. The title faded in: The Long Day Closes. I went in trying to escape my life. What I found helped me understand my life instead.

The film language of Terence Davies is unique from any other filmmaker—enough to transfix any new viewer living in a personal world that is yet to be inhabited by his vision of cinema. Inspired by musicals of classic Hollywood like Singin’ in the Rain and Young at Heart (starring his idol, Doris Day), Terence takes the idea of memory and curates it to a visual form. Tracking shots represents the past and the future, varying where the camera moves with the movement of time. Dissolves represent a shift in time and memories overlapping atop each other, giving 96 frames in total to represent two memories in conversation with each other.

At heart, though, Terence Davies was a musical filmmaker. His visual compositions and how they were arranged in the edit are artistically equivalent to any great Mozart symphony. But more important than this is how he incorporates music into his cinema. The Long Day Closes, while acting as a memory collage, simultaneously acts as a musical collage—alluring your ears with a 40’s and 50’s-inspired non-diegetic soundtrack, along with allusions to other films. As the camera tracks left to right into a snowy alley, Orson Welles chimes in from The Magnificent Ambersons; or as the door closes on a young couple, giddy inside from their blossoming romance, Tom Drake and Judy Garland narrate the scene, taken from Minnelli’s Meet Me in St. Louis.

To any young cinephile striving to tell their own stories in art, the strength of Davies’ voice is enough to influence the untutored eye toward his art. But as a young boy, I saw myself within Bud. Based on the childhood of Terence Davies, we revisit his personal memories through the character of Bud. His family is a protective source in his life, bringing joyful times and fulfilling him, but he is tortured by his flowering identity. In Bud’s—and by extension, Terence’s—life, it was his identity versus Catholicism. In mine, it is my identity versus the society I had built up in my mind to surround me.

I grew up like Bud, surrounded by a strong community. My mother was a caring source in my life. My father provided positive guidance for me as a growing boy. My sister allowed me to supply her with the life lessons I had continued to learn. Through childhood, she had struggled a lot, and my parents weren’t always able to care for me, but I found solace in the second family we had built with the people in our town. My cup was overflowing with water, always filled by the kindness and warmth of those around me. We’d gather and play and sing, just as Bud’s community did. It was home.

In seventh grade, I began to internalize my attraction to the same sex. There was a boy in my class who I was close friends with. He was gay as well. I loved him, but never made any moves out of fear of losing that friendship. Through long talks, we understood ourselves and our sexuality. Into the next year I had developed a queer community around me. There was a warmth to my friends; I felt comfortable with the people I identified myself with. When I transitioned from middle school to high school, I came out publicly as gay. To be accepted by all of my peers felt like I was finally home. I was supported and welcomed, still viewed as an equal. My soul was strong moving into high school, but I met a personal crisis once I arrived.

Over the first few months, I realized that though I was attracted to men, I was still attracted to women, too. I developed a crush on a close female friend of mine, who was there for me in a dark period of my life. I felt as though I bore a scarlet letter on my chest, though I shrouded it so no one could see. The shame grew in my body. I had declared to the world that I was gay, now I realized that the identity of “gay” no longer fits me. How was I to carry on as an individual if my external identity was a lie? It didn’t help that the boy I fell in love with had moved on, and we no longer spoke. In crisis, I cut off all of my friends. I isolated myself from the world. I felt I had done a great disservice to the queer community that embraced me. So, in shame, I left them.

I hated myself; I hated my sexuality. I repressed it and buried it deep down, which began to destroy me. For two years, I was alone. I had no friends. At lunch, I’d sit in the hallway by the cafeteria alone. The only joy I found in life was through the cinema, like Bud. That’s the time I fell in love with the movies. I do not regret this period of discovery with my love of cinema, but I recognize it was a sliver of joy in a life no longer worth living.

During the height of the COVID pandemic, I began to turn my life around. With the time away from humanity, I learned to live as myself and be content with my life. I met someone who I fell in love with, and I was able to better accept my identity; but the relationship was unhealthy, and only recently have I been able to accept the internal abuse and emotional damage that it left me with.

With all the baggage I carried, to be embraced in the arms of Terence Davies’ cinema gave me the power to accept myself and free myself of the shackles I had placed upon my wrists. I was Bud, a young boy destroyed by his own conscience. It was an awakening, and on this day filled with emotional turmoil, I found a home in the comfort of The Long Day Closes. The film gave me hope that I had the strength to accept myself and live my life true to myself. I do not know where Bud’s life went after the sun set on the long day, but I knew I did not have to continue being ashamed of myself. I knew that I could lead a life free of pain.

It has been two-and-a-half years since I discovered The Long Day Closes. After seeing the film, I soon ended my relationship with the person I was with. We were bad for each other, and I knew we needed to stop attempting to make it work and just accept that it wouldn’t. My sister left the hospital soon after, and since then, she’s become a new person. A year after, we cried in my car, because she became a person I could not imagine her becoming a year ago; healthy and full of life. I was so proud of how far she had come. I still am. If she could change, I knew I had that power too. I moved to New York for school within a year’s time, and fell in love with my boyfriend. He’s helped me become the person I wish I could have been when I discovered The Long Day Closes. I love him immensely and could not be more content with my life. I don’t place a meaning on my sexual identity. The labels of sexuality have tortured me inside, and so I no longer define myself. I am purely me, and that’s all I want to be.

Terence Davies gave me the resources to become a better person. He is the reason I am the man I’ve become today. Within the months after seeing the film, I sent Terence a letter, thanking him for his impact on my life. The next morning, I received a video back from Terence. He thanked me for the letter, admitting it made him break down in tears, saying he had never received a letter thanking him for his art that brought him such emotion. With that video response back, I returned the favor by breaking down in tears.

It has been a month since his passing. I found out two minutes after it was announced, the day after revisiting The Deep Blue Sea on 35mm with my friend Brian (another soul indebted to the cinema of Terence Davies). I was heartbroken. I miss him dearly. Without knowing it, he provided me with the life I have today. I still need him now. He may no longer be with us, but the work still stands, and The Long Day Closes will forever be as important to my life as it was when I first watched it.

If there is a silver lining to his passing, it is this: I had long claimed Terence Davies to be the greatest living filmmaker. That is no longer the case. Now, he is the greatest filmmaker to ever live.

Words By Matt Haller