The Gospel According to Paul Morrissey

Interview Magazine and Roxy Cinema present a new series focusing on the provocative figure behind Andy Warhol.

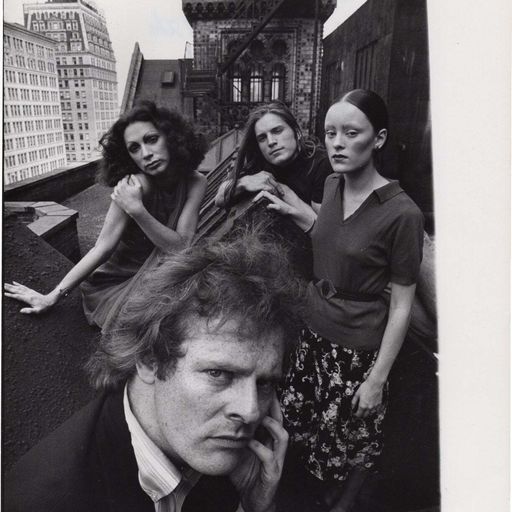

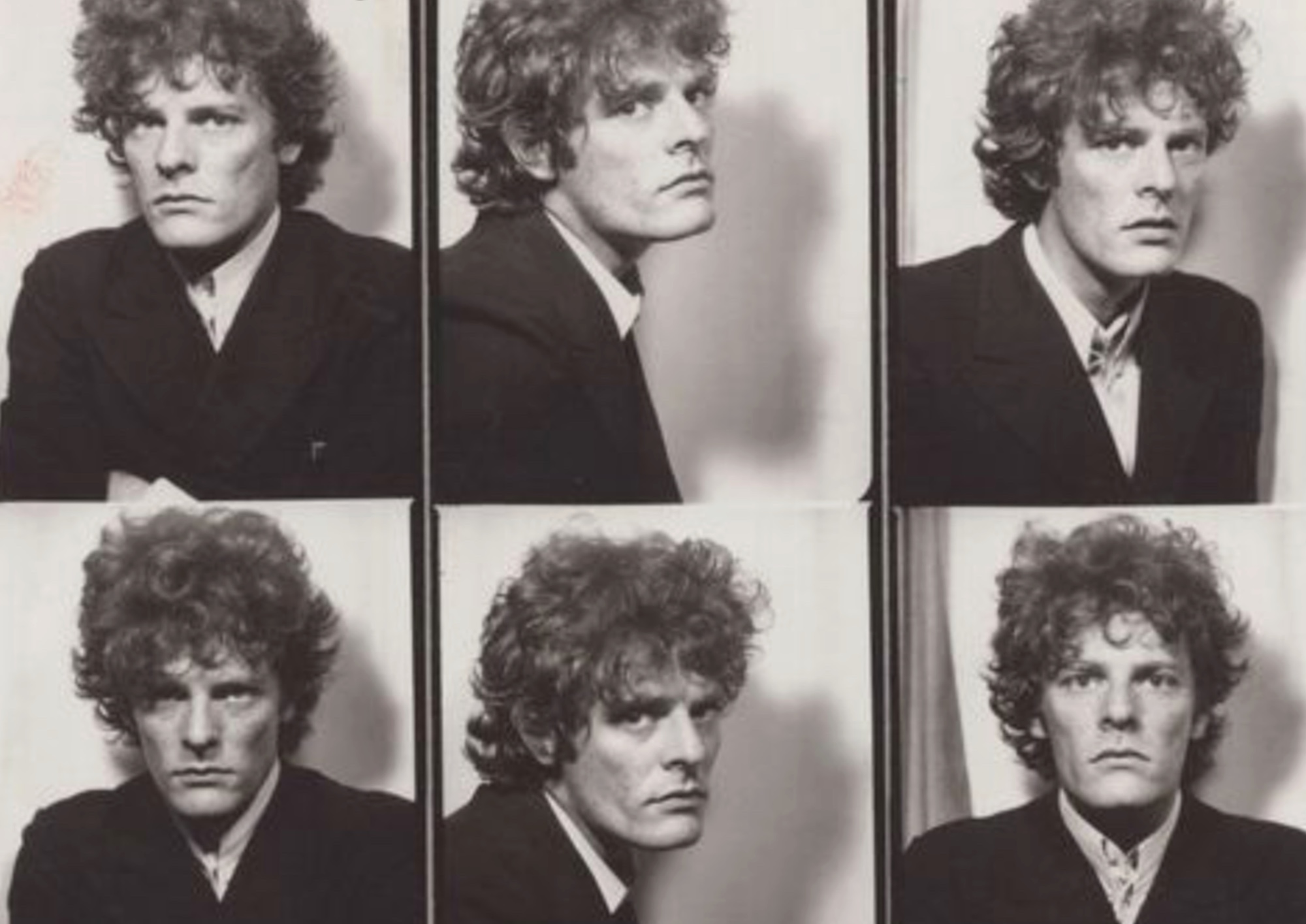

Paul Morrissey Photo Booth Photos from The Factory Photo Booth, Courtesy of Paul Morrissey Archives.

The series brings together a selection of films across three decades of the director’s filmmaking career, from his collaborations with Warhol to his solo features of the 1980s, including the SoHo premiere of one of Morrissey’s most personal and seldom screened films Beethoven’s Nephew (1986) starring Dietmar Prinz, Jane Birkin and Nathalie Baye.

_____

“He makes a marvelous kind of world, and a marvelous kind of mischief, holding nothing back and just watching it happen. . .”Personal expression” is a much abused expression, but these films are real expression. . .Nobody has done anything like it. The selection of people, the casting, is absolutely brilliant and impertinent. The life they see, the gutter they see, or the world they see is so funny and agonizing, and they see it so vividly, with such humor. . .such original humor. . .” – George Cukor on Paul Morrissey

______

June 1965. A seismic month in the underground history of the world: Bob Dylan records “Like A Rolling Stone”, the International Poetry Convention brings together the American and European Beats at the Royal Albert Hall, and Gerard Malanga introduces filmmaker Paul Morrissey to Andy Warhol.

When Morrissey entered the E. 47th St. Factory, Warhol was already one of the most consequential and focused upon artist-personalities of the era, comparable in America only to Dylan. His film experiments (Sleep, Empire, Blow Job, Vinyl, Poor Little Rich Girl) enshrined a growing influence beyond the confines of the art world with Warhol’s self-perpetuated momentum dependent as much upon conceptual ingenuity as it did on a massive influx of exposure, outrage, and the sine qua non for lasting success in New York City: money. Enter filmmaker Paul Morrissey, a Yonkers raised, can-do polymath for whom Hollywood in the 1930s was Valhalla. Fresh out of Fort Dix where he earned the rank of First Lieutenant, Morrissey spent the early part of the 1960s making short, silent comedies while owning and operating the Exit Gallery, a nickelodeon style cinema on E. 4th Street that exhibited the first films of Brian De Palma, among others. Impressed with Morrissey’s resourcefulness and ability to properly focus a 16mm camera, Warhol offered him an opportunity to assist with the films being made at the Factory. Morrissey came to work every day from 1965 – 1973, acting as the de facto publicity and distribution manager at the Factory, co-conceiving (and naming) Warhol’s traveling multi-media roadshow The Exploding Plastic Inevitable featuring The Velvet Underground and Nico (who Morrissey managed during their first year at the Factory) and co-founding Interview Magazine with John Wilcock and Warhol.

For nearly a decade, Warhol and Morrissey functioned something like twin-brains with a single-minded purpose: recreating in New York City the Hollywood studio system of the 1930s and 1940s via the Factory. The relative success of Chelsea Girls gave rise to Andy Warhol Films, Inc., an independent filmmaking studio and distributor that began producing what Morrissey characterized as “comedy of manners”. Shot without a script and very little money, I A Man (1967), Imitation of Christ (1967), Bike Boy (1967), Loves of Ondine (1967), Lonesome Cowboys (1968) and San Diego Surf (1968) satirized sex, drugs and the social mores of 20th Century American life, fueled by Warhol and Morrissey’s determination to capsize the fashionable notion of film as a “director’s medium”. “To me,” Morrissey told British Vogue in 1978, “moviemaking is dealing with personalities, people who are always the way they are in every film, like John Wayne or Clint Eastwood, that kind of film-star personality which is not very fashionable now. It doesn’t really matter what the camera’s doing as long as the people are worth watching. . .”

After the attempt on Warhol’s life by Valerie Solanas in June 1968, Morrissey began directing features on his own under the Warhol banner (“Andy Warhol presents. . .”), aspiring to the heights reached by his cinematic forebearer and friend George Cukor, an “actor’s director” with few equals, who shared with Morrissey a belief that movies are, first and foremost, a performer’s medium, one that lived or died with an audience’s interest, empathy, and fascination with the personalities they encountered on screen. Just as decades earlier Greta Garbo, Jean Harlow and James Cagney captured the movie going public’s imagination, Morrissey promoted his own on-screen troupe of self-invented Superstars for the 1960s and 1970s: Viva, Candy Darling, Joe Dallesandro, Jane Forth, Jackie Curtis and Holly Woodlawn. With Flesh (1968), Trash (1970), Women In Revolt (1971) and Heat (1972), Morrissey’s determinedly populist gambit paid off: the critical and commercial success of these films made Joe Dallesandro and Candy Darling counterculture icons; the extraordinary prescience of these films prefiguring virtually every turn in fashion, style, and culture over the next 50 years. “I think it’s funny,” Morrissey told an interviewer in 1980, “that a person like me, who’s basically kind of square, should be the only one who really left a record of a kind of strange world during a certain period of time that nobody else dealt with.”

After the international success of Morrissey’s Flesh for Frankenstein (1973) and Blood for Dracula (1974), filmed back-to-back in Rome and starring Dallesandro alongside another Morrissey screen discovery Udo Kier, he left the Factory and turned his attention to gothic horrors closer to home, a trilogy of films set in New York City and its outer boroughs: Forty Deuce (1982), Mixed Blood (1984) and Spike of Bensonhurst (1988). Dark comedies exploring the failures of liberalism and the utopian dreams of the 1960s, these films, among Morrissey’s best, offered a new coterie of Morrissey Superstars for the 1980s: Marília Pêra, Rodney Harvey and Sasha Mitchell. When critic Jonathan Rosenbaum asked Morrissey why he portrayed drug addicts and street hustlers so sympathetically despite his own personal convictions as a lifelong conservative Catholic, he responded:

“A human being is a sympathetic entity. No matter how terrible a person might be, someone with an artist’s point of view will try to render his individuality without condescension or contempt. That’s the natural function of a dramatist. The movies I’ve made have no connection to my personal beliefs. They don’t say, ”Do this,” or “Don’t do that.” They portray a kind of emptiness in people who are living through a transitional cultural period when they don’t know who they are or what to do.”

The Gospel According to Paul Morrissey, brings together a selection of films across three decades of the director’s filmmaking career, from his collaborations with Warhol to his solo features of the 1980s, including the SoHo premiere of one of Morrissey’s most personal and seldom screened films Beethoven’s Nephew (1986) starring Dietmar Prinz, Jane Birkin and Nathalie Baye.

My Hustler (1965) Dir. Andy Warhol

Filmed over the Labor Day holidays of 1965, My Hustler belongs to a period of transition for the Andy Warhol Cinematic Universe. Collaborators such as Chuck Wein (credited here with “written direction”) and Paul Morrissey (behind the increasingly mobile, sync-sound 16mm camera) were moving the Factory production away from single-take, silent films and into more complex arrangements featuring actors, dialogue, and feints at narrative situations.

My Hustler consists of two extended conversations, first as a Fire Island host (the outrageously camp Ed Hood) contemplates the recumbent figure of the beach Adonis (Paul America) he has hired for the weekend, and then as the newcomer learns a few tricks of the trade from an older colleague “Joe” a/k/a Sugar Plum Fairy. A hit in its midnight engagement at the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque, My Hustler became one of the first Warhol films to escape the downtown orbit and open at a commercial theater in midtown, where it was reliably panned as “sordid, vicious and contemptuous” by Bosley Crowther of the New York Times. – Dave Kehr, MoMA

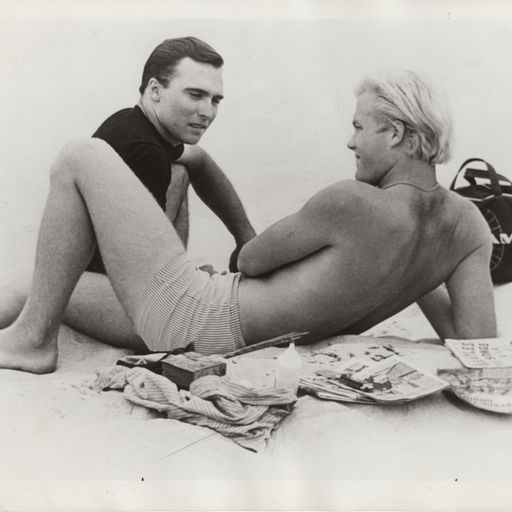

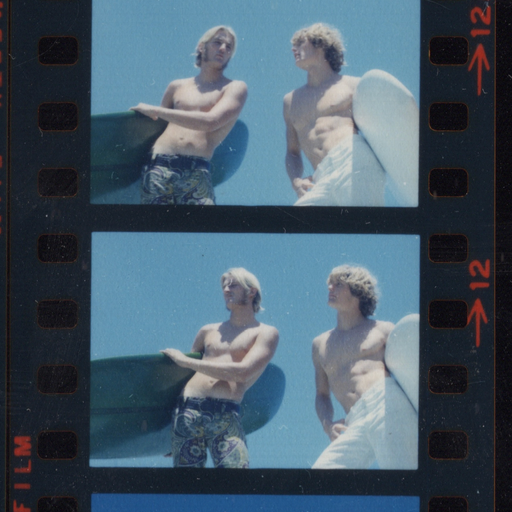

San Diego Surf (1968) Dir. Andy Warhol

A comedy of muddy morals set against the tropically clear, aquamarine shoreline of La Jolla, California, Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey’s San Diego Surf centers on the mismatched passions of Susan Hoffmann (Viva), a “nice, normal middle-class housewife with a penchant for surfers,” and her estranged, openly gay husband Mr. Mead (Taylor Mead). Desperate to ingratiate themselves with the town’s hoi polloi, our debauched protagonists decide to rent their summer home to a gang of beach bums played, not unconvincingly, by Joe Dallesandro, Tom Hompertz, Michael Boosin, and Louis Waldon. “If we become surfers,” Mead insists, “our status would change. We are just golfers . . . second-class citizens.”

The screwball plot belies the film’s dark send-up of a society obsessed with the power of celebrity and those who possess it. Set apart by their youthful beauty and vitality, Warhol and Morrissey’s sun-kissed bottle-blonde surfers don’t say much; they don’t have to, they are the aesthetic justifications of their own existences. Plied with Viva and Mead’s worshipful veneration, the surfers coolly luxuriate in their own aura, unleashing the sadomasochistic desire within the action that culminates in a perverse baptism. “I’m a real surfer now,” Mead cries rapturously in the film’s final moments, “a real surfer.” – Michael Chaiken, Film Comment

Chelsea Girls (1966) Dir. Andy Warhol

Warhol’s epic double-screen masterpiece, the Gone With the Wind of New York’s ‘60s underground, was filmed throughout the summer of 1966. After shooting several films featuring his Superstars and friends, Warhol got the idea to unify all the pieces of these people’s lives by stringing them together as if they lived in different rooms of the Chelsea Hotel. Chelsea Girls, one of Warhol’s most ambitious and commercially successful films, is a brilliant example of the artist’s signature technique of assembling complete reels of unedited film in various ways. “In one film alone,” an early reviewer noted, “Warhol has sadism, masochism, whipping, transvestites, homos, prostitutes, a homosexual ‘Pope’, boredom, stunningly beautiful girls, depravity, humor, ‘psychedelics’, truth, honesty, liars, poseurs. . .” i.e. the whole wide world.

With Brigid Berlin (Brigid Polk), Susan Bottomly (International Velvet), Ari Boulogne, Ronnie Cutrone, Angelina “Pepper” Davis, Donnie, Eric Emerson, Patrick Fleming, Ed Hood, Gerard Malanga, Marie Menken, George Millaway, Mario Montez, Nico, Ondine, Ronna Page, Rene Ricard, Ingrid Superstar, Mary Woronov (Mary Might).

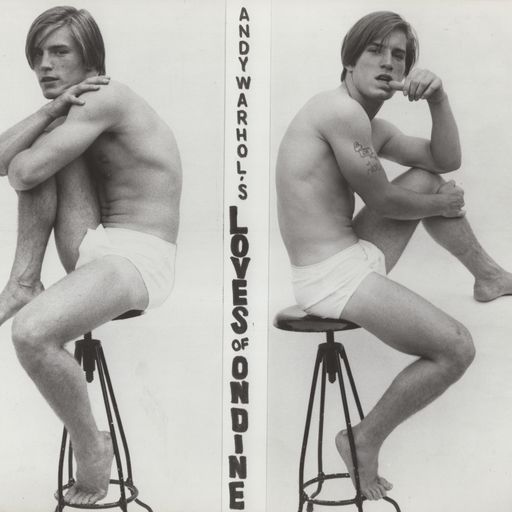

Loves Of Ondine (1967) Dir. Andy Warhol

In his star turn as a leading man, “the underground’s greatest dramatic actor” Robert Olivo, a/k/a Ondine, exudes serial killer charm (think Satanic Michael Nesmith) in a series of “encounters” with the opposite sex. Despite Viva’s best effort, none seem to dent his fidelity. Could it be congenital? Or something far more sinister? Flash cut to the woods of East Hampton where Rolando Peña, Founder and Director of the Foundation of the Totality, and the Banana Cuban Boys perform a Happening called “The Paella-Bicycle-Totality Crucifixion”. Huh? Enter Joe Dallesandro in his first ever Warhol film appearance. Together with Ondine the duo re-enacts Gorgeous George vs. Dandy Dan Miller at Madison Square Garden. Call in the calvary: Brigid Berlin puts the bow on this fucker by way of epic bitch-fest. One of the oddest entries in the Warhol/Morrissey sexploitation canon, a film that posits the notion that everything we know about the “sexual revolution” of the 1960s is probably wrong and definitely stupid. Not to be missed.

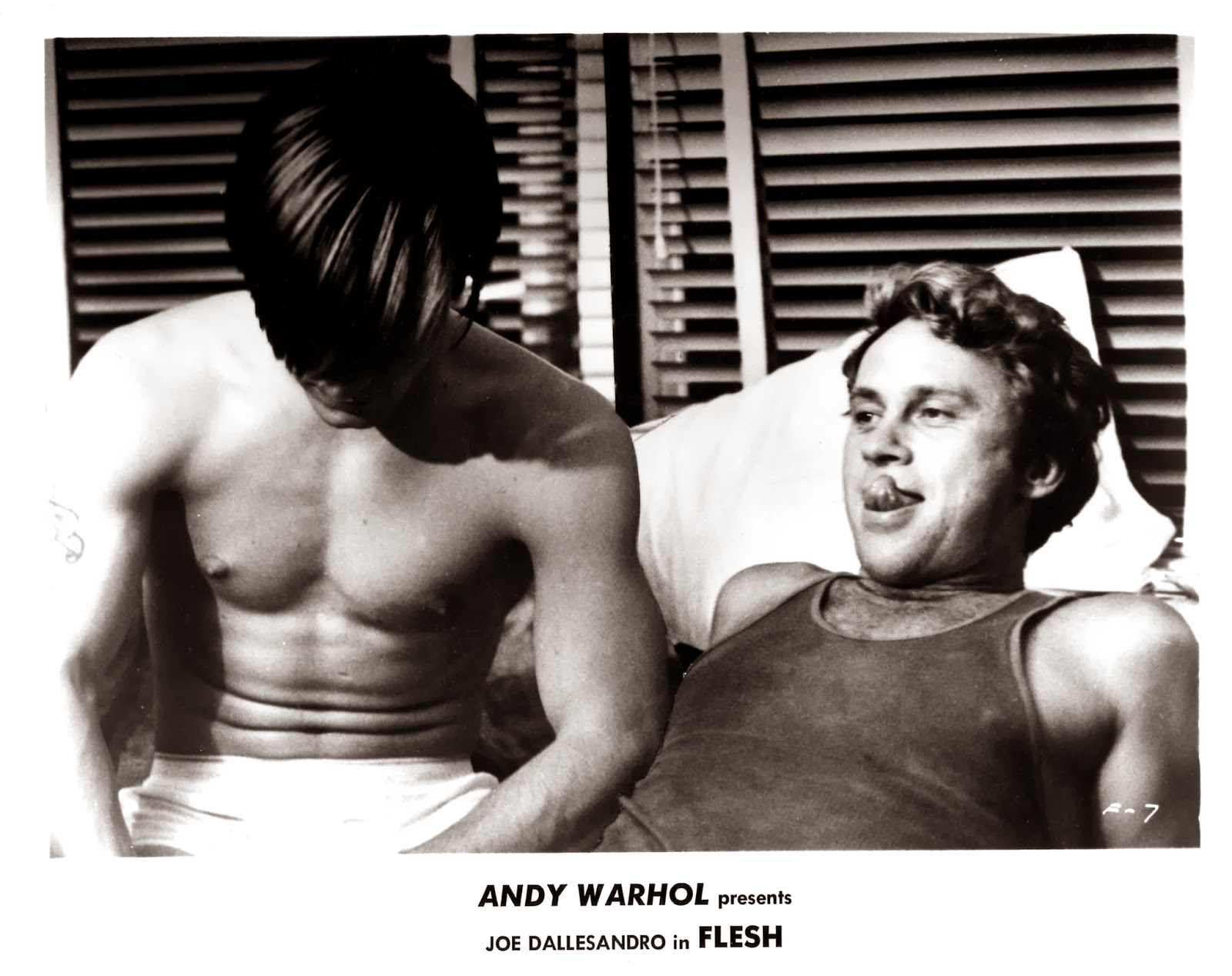

Flesh (1968) Dir. Paul Morrissey

Initially conceived to beat John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (1969) to the box office, Morrissey’s directorial feature debut is a defining moment in American independent cinema. Produced for $4000, the film follows a day in the life of Joe whose girlfriend kicks him out of bed and onto the streets to make some money to help pay for her girlfriend’s abortion. What follows are a series of encounters with johns, including a gymnast (Louis Waldon) and an artist played by former silent film actor Maurice Braddell. But the threadbare plot belies something far deeper and funnier in Morrissey’s unsentimental, accepting attitude toward life, perfectly embodied by Joe Dallesandro’s brooding, disaffected performance.

“In Flesh, the man at the end talks about the wound he’s got on his arm, that his flesh is scarred, and he’s going to pot and getting fat by not going to the gym. One girl wants an abortion- wants her flesh removed. Everyone is in a predicament relating to their flesh. Joe’s predicament is that his flesh is attractive. It was all very deliberate. . . “ – Paul Morrissey

Spike of Bensonhurst (1988) Dir. Paul Morrissey

Welcome to Bensonhurst, a nice Italian neighborhood in Brooklyn. A place for families (it takes care of its own), a place with traditions and rules: “family” rules that are not made to be broken. Taking a satirical look at the rise of an ambitious street kid and amateur boxer, Spike Fumo, played with gusto by Sasha Mitchell (Kickboxer), Morrissey’s comedic portrayal of the erosion of traditional values shows how something as dependable as organized crime is getting very confusing. When asked by the failing New York Times how he could portray the Mafia with such sympathy, an organization that keeps drugs out of its own neighborhood, but has no qualms flushing them into others, Morrissey replied, “Hey, it’s better to have double standards than no standards. . .”

Mixed Blood (1984) Dir. Paul Morrissey

If, in 2024, Alphabet City resembles nothing so much as a retirement community for twenty-somethings, flashback forty years when all was going well for the thriving drug trade on New York’s Lower East Side—police, suppliers, and dealers had an arrangement that satisfied all, minimizing competition and maximizing profits. The last thing anyone wanted was a challenge to the system—a drug war in the streets. The last thing anyone expected was Rita La Punta and her gang of fifteen year old hoodlums—“the Maceteros”. “Life in a liberal toilet. . .” was how Morrissey characterized this funny, shocking, devastatingly ironic view of big city living. Marília Pêra (Pixote), Morrissey’s professed favorite actor, brilliantly portrays Rita La Punta, whose ambition and jealousy dominate the life of her son Thiago, played by Richard Ulacia alongside a group of newcomers (many cast from the streets) including the late Rodney Harvey. When a parent is asked in Mixed Blood, “Do you know where your children are?”, he replies, “I don’t know who the fuck my children are.” This ain’t the world of C. Aubrey Smith, Queen Victoria and Ronald Reagan. Welcome to what used to be New York City.

Beethoven’s Nephew (1986) Dir. Paul Morrissey

Any study of Beethoven, portrayed here by Wolfgang Reichmann, tends to avoid the extraordinarily miserable and pathetic character of the man, a personality so petty, mean, and spiteful that he was incapable of habitation amongst ordinary people. With no real enemies in the world, he created them, becoming his own worst enemy and a victim of his imagination, obsessions, and misanthropy. Using Beethoven’s own words (Morrissey insisted that the screenplay, co-authored with Mathieu Carrière, conform strictly to historical truth), Beethoven’s Nephew turns a cynical, respectful eye on the composer who made it his life’s duty to take away from his sister Johanna (Jane Birkin) her only son Karl (Dietmar Prinz). “We must get used to the idea that genius has nothing to do with everyday life. It exists on another level. Great artists seldom have noble souls.” – Paul Morrissey

Words By Michael Chaiken

Beethoven's Nephew, Courtesy of Paul Morrissey Archives