Dream States: The Cinema Of Gus Van Sant

One of the most distinctive and daring voices in American filmmaking takes centerstage at Roxy Cinema this winter.

In anticipation of director Gus Van Sant’s upcoming release, Dead Man’s Wire, we’re revisiting a wide range of his films — from cult landmarks to studio triumphs to meditative experiments — each revealing a different facet of Van Sant’s evolving vision of America.

The series opens with Drugstore Cowboy (1989), the breakthrough that introduced Van Sant’s poetic realism and sensitivity toward outsiders. Matt Dillon delivers one of his defining performances as the leader of a drifting group of addicts, portrayed with empathy, grit, and an unexpected grace.

From there, we dive into the wild, off-kilter energy of Even Cowgirls Get the Blues (1993), Van Sant’s adaptation of Tom Robbins’ cult novel. With Uma Thurman as the hitchhiking heroine Sissy Hankshaw, the film embraces the eccentric, the surreal, and the rebellious spirit of early ’90s counterculture.

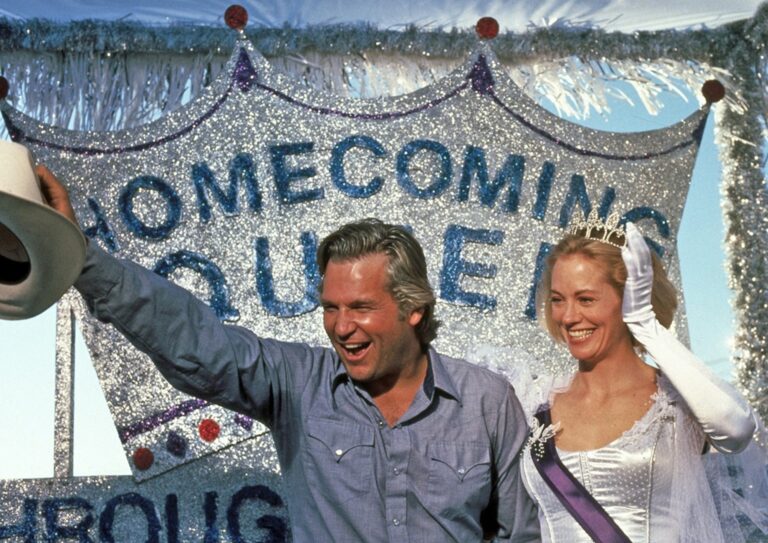

Van Sant’s sharp wit and satirical edge shine in To Die For (1995), starring Nicole Kidman as an ambitious small-town weather reporter whose desire for fame veers into the sinister. The film’s blend of tabloid Americana, dark humor, and media obsession feels even more pointed today.

We’re also revisiting the career-defining success Good Will Hunting (1997), the heartfelt story of a troubled mathematical prodigy from South Boston, played by Matt Damon, whose life opens in unexpected ways after meeting a compassionate therapist (Robin Williams). It remains a touchstone of ‘90s cinema and one of Van Sant’s most beloved works.

At the turn of the millennium, Van Sant shifted boldly toward a new, minimalist style. The retrospective includes Elephant (2003), his Palme d’Or–winning meditation on a day at an American high school before a tragic act of violence. Its long takes, quiet observations, and understated performances create a portrait of youth that is both haunting and humane.

Alongside it, we’re presenting Last Days (2005), a loosely inspired portrait of Kurt Cobain’s final days. Sparse, atmospheric, and deeply interior, the film continues Van Sant’s pursuit of stories told through gesture, silence, and the rhythms of isolation.

Van Sant’s adventurous spirit is also on display in his shot-for-shot reimagining of Psycho (1998) — a cinematic experiment that remains one of the most debated films of its era — and in Promised Land (2012), a thoughtful, contemporary drama about fracking, corporate persuasion, and small-town struggle.

Together, these films paint a vivid portrait of a director who has never stopped reinventing himself, moving fluidly from intimate dramas to genre experiments, from pop surrealism to stripped-down realism. Seen in sequence, they offer a rare chance to trace Van Sant’s shifting perspective on America: its myths, its margins, and the restless spirit running through it all.

We invite you to join us throughout the retrospective as we revisit these remarkable works on the big screen. And in January, we’ll welcome Gus Van Sant in person to celebrate the enduring legacy — and exciting future — of his filmmaking.

Ahead of the Retrospective Cinema Director Illyse Singer interviewed Gus Van Sant about his filmmaking career.

Looking across your career, what feels most different to you now about the way you approached filmmaking early on versus today?

I think the films have different stories and concepts, so there hasn’t been a particular quality that through the years have changed, so the earliest ones feel like they were approached according to the story – there are always different results, but the approaches are similar.

Is there a film in your body of work that you think audiences understand differently now than when it was first released?

All the films kind of go in and out of different receptions (at least the ones I hear about ) different generations have related differently

How much do you rely on intuition versus structure when you’re developing a film?

Hmm, intuition and structure can work together. Intuition sometimes feels like something is coming from outside what would seem like a structure of cinematic generalities, but the structure itself can be intuited.

Many of your films center on characters who exist on the margins. What draws you to those stories?

I think that it is a storytelling convention – and a lot of times is is about characters on the margins, but they have learned and developed a family who together are existing together as outsiders.

Were there artists or filmmakers early in your career who gave you permission to make the kinds of films you wanted to make?

There are a lot of different inspirations – but some earlier ones were by filmmakers who were way outside the normal filmmaking world, like John Waters or John Sayles, or John Cassevettes or Andy Warhol. Filmmakers who were just getting a hold of a camera and making a film, outside of Hollywood.

How have your collaborations with actors evolved over time, especially with performers you’ve worked with more than once?

Yes some of the actors that I have worked with before are used to whatever system I have going, so that can be fun.

What still excites you about filmmaking after all these years?

I still get inspired by a new place of a group of people that I want to get to know.

What advice would you give to filmmakers trying to balance personal vision with the realities of the industry today?

There are a lot of ways to make a film now, the advice would be just go for it – not that it isn’t hard, but there are less obstacles.