Eve Arballo On Normal Love

The Film-makers’ Cooperative, the Museum of Sex, and Roxy Cinema New York present a one-time screening of Jack Smith’s Normal Love (1963) as part of the Carnal Screen Series.

The Film-makers’ Cooperative, Museum of Sex, and Roxy Cinema New York are pleased to present a one-time screening of Jack Smith’s Normal Love (1963) on Sunday, August 28th at 3 PM as part of the Carnal Screen Series. Eve Arballo, curator for the Museum of Sex, discusses the significance of Normal Love with The Cinephile. Buy Tickets for Normal Love HERE.

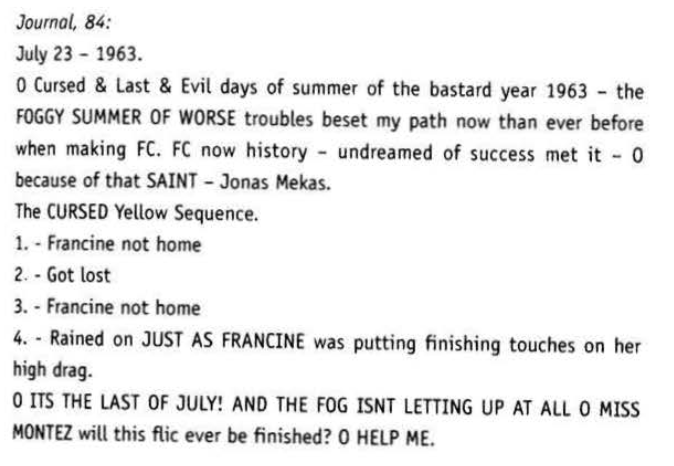

On a day much less muggy than those preceding and those following it, on July 23, 1963, Jack Smith penned the above in his journal. His melodramatic decree of the FOGGY SUMMER OF WORSE cursing his path forward centers on his perceived failure of FC (Flaming Creatures) which had premiered at the Bleecker Street Cinema just a few months earlier on April 29th. The audience was exposed to a litany of orgiastic images: of men and women in dresses and makeup, disorienting shots of eyes and lips, piles of limbs, and genitalia. That night, the police were called, and the film was seized. The following March 1964, Flaming Creatures would become the cause célèbre of the underground film movement when it would be ruled to be in violation of New York’s obscenity laws, resulting in the arrest of fellow filmmakers Ken Jacobs and Jonas Mekas.

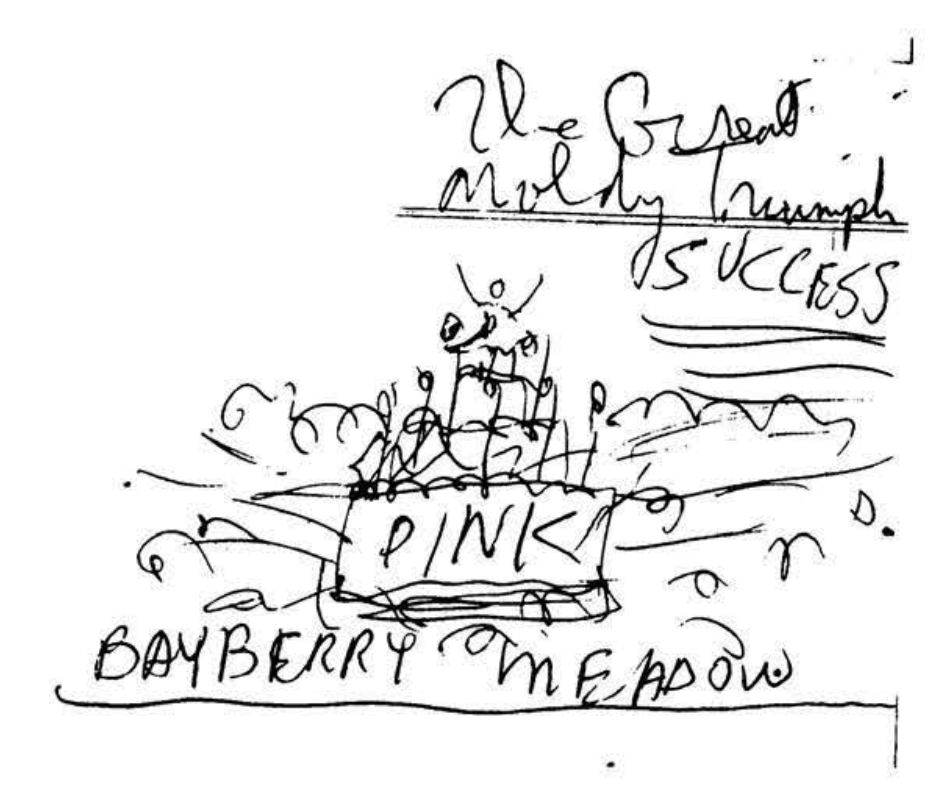

After the scandal caused by Flaming Creatures in New York City, Jack Smith radically resolved from this point on to never again create a completely finished film, an idea that came partly as a solution to the constant threat of his films being seized (if a work was shown as a work in progress rather than a completed project, Smith could reliably use the excuse that the scenes of obscenity could be removed) and partly as a result of his persistent perfectionism. A profound anti-capitalist, Smith’s decision to never again complete a film can be read as an act of noncommercial rebellion, a furthering of both his queer anarchism and resistance to making work that is easily consumable and disseminated. “I want to be uncommercial film personified,” Smith once said. Not only had he been deprived of an audience for his films, he had become cynically aware of the power of the censors. To ensure that people could see his films, his ultimate goal, Smith decided to make his next film more approachable. In the summer of 1963 he began filming his next project, with color film supplied by Jonas Mekas. Working under the title of The Great Pasty Triumph, Smith spent his summer in Cherry Grove, New York, at the house of socialite Isabel Eberstadt “shooting a lovely, pasty, pink and green color movie that is going to be the definitive pasty expression.”

Smith’s pasty project was Normal Love, a never-completed work that was filmed over the course of a year. The film is roughly broken into six sequences with a very loose plot and little to no clear narrative. Visually, Normal Love is lush, verdant, and awash with Smith’s pinks and greens; his use of color along with his compositional technique gives the entirety of Normal Love an utterly otherworldly feel. Normal Love is very similar to Flaming Creatures with the orgiastic layering of bodies and limbs in close, cropped shots, and its use of fabric, scarves, and smoke which function as a scrim and create further depth and dimensionality. With very little in the way of funding or special effects, Smith transports viewers to a pasty, atmospheric realm.

Pasty is a word Smith uses frequently in reference to Normal Love, and while he never outlines what exactly it means or if it’s a person (there is a character called Uncle Pasty, after all), color, thing, or simply a mood, pasty is at least some of the time a shortening of the word pastoral. Normal Love, with its clear setting of the countryside in the summertime, has a distinctly bucolic quality to it. Notably inspired by Baroque and Rococo artists such as Jean-Antoine Watteau, Smith applied principles from the fêtes galante style, featuring elaborately costumed characters in idyllic scenes and enacting the recreation of mythologized worlds (Normal Love takes place in an Atlantis of sorts). The swing scene featuring the Watermelon Man and the Girl resembles in both color and composition The Swing by Jean-Honoré Fragonard. Rococo as a movement, too, embodies much of the affect of Normal Love: its freedom from standardization and tradition, the unbearable, triumphant lightness and enjoyment of life epitomized by its scenes, and its celebration of love and pleasure.

Contrasting with the abundance of nudity and eroticism in Flaming Creatures, Normal Love only has two moments of explicit nudity, one of which takes place in a milky bath with a cobra, and the other on a cake (the Great Pasty Birthday Cake) crafted by sculptor Claes Oldenburg. The nudity in the latter scene was actually an accident—the actor who plays Uncle Pasty forgot to bring his costume, and since the scene was so deep in the woods there was no time to run and grab it.

From its release in late 1963 to 1965, Smith screened rough cuts of Normal Love at the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque and the loft of fellow filmmaker Ron Rice. During screenings, Smith would edit the film directly from the projection booth, often extending the duration of screenings to last as long as four hours. Ten years after Smith’s death from AIDS-related pneumonia in 1989, J. Hoberman and Jerry Tartaglia presented a program of Smith’s films at the Museum of the Moving Image, including a presentation of the newly restored Normal Love, which Tartaglia painstakingly restored based on the cues that Smith had written for the soundtrack. Tartaglia, who identifies himself as a “living slave” to Smith’s œuvre, also testifies to his creative genius. Jack Smith, whose work has seen obscurity and decades of institutional silencing, has in recent days come to the public once more with a screening of Flaming Creatures as part of the Carnal Screen series, and more recent screenings of Normal Love at the Film at Lincoln Center and now at Roxy Cinema New York.

–Eve Arballo